I can’t say that the cover of Dragon Magazine #107 (March 1986) inspires many memories of its contents or putting it to use. In fact, as I opened it up for the first time in two and a half decades (or longer), I was sure it would be a quick overview of stuff that didn’t mean much to me then or now. Yet, once I started perusing it, I realized there was a lot more in there that I had found useful back in 1986. It was just that the cover itself never lit a fire in my mind.

Speaking of that cover, like several of the issues of Dragon I have written about for this series so far, my copy’s cover is detached.

The image, which is in a chiaroscuro style, is by Dean Morrissey and depicts a gnome juggling glass and/or metallic orbs (I can’t tell) by a gnarly tree for a skulking crowd of other gnomish folk. Entitled “Gargoth Disguised,” the artist provides an explanatory note that says the “magnetic, benevolent, and magical traveler[‘s]…temporary persona belies the sinister character beneath.”

That is all well and good, but aside from the overly dark rendering of the cover image, there is nothing to convey that to the reader without the note. In other words, it is still not a cover that does much for me.

Editor-in-Chief Kim Mohan’s editorial note this month announces a forthcoming new magazine “filled entirely with modules.” That’s right! We’re getting into the era of my personal favorite D&D related periodical, Dungeon Magazine (even though at this point it remained untitled). According to Mohan, the new mag will come out every other month and will start off as subscription-only and won’t be available in stores. This latter detail must have not been the case for very long because I remember buying Dungeon #5 at the Compleat Strategist (where I bought the vast majority of my gaming materials at that time), so it was available in stores 10 months after its debut (at most).

This announcement also includes a note that Dragon Magazine will no longer be including adventures as “special attractions.” This would turn out to not be 100% true since there would still be a handful of adventures (wrapped in pages to identify them as a Dungeon Magazine insert) printed in future issues I still own. At the time, however, I remember being very skeptical of this new endeavor. I did not want to have to buy two magazines and I was not sure there would be enough quality submissions to support a whole magazine, even if it only came out six times a year. Ultimately, I would come to love Dungeon more than Dragon, and while, sure, not all of what was published in Dungeon can be called “quality,” most of it was at least useful as a source of ideas to mash together and adapt to make new adventures, which is how I still use my extensive (but sadly, still incomplete) collection of Dungeon mags.

Moving on, this issue’s installment of The Forum is as boring as I have found most of them in retrospect, save perhaps for one letter from Daniel Myers from Lansing, Michigan. In it, Myers complains that “all new rules seem to be bound to Mr. Gygax’s own Greyhawk campaign.” This is a topic I brought up in my overview of Dragon #94 and Gygax’s “Official Changes for Rangers,” wherein he provides several pages of tables for how he purported to run rangers in his home game. While Myer’s letter is in response to Gygax’s article from Dragon #103 on the future of the game and the second edition he would never get to realize, the aforementioned article does seem like evidence of what he calls the “creeping co-opting of the individual’s creative input.” In other words, the assumption that what was good for Gygax’s own games was good for everyone’s games. The irony of course is that even Gygax himself didn’t use most of these rules and supplements. Of course, this concern would soon become moot given that we are very close to Gygax’s ouster and the diminution of Greyhawk’s influence on the game as Ed Greenwood’s Forgotten Realms became D&D’s standard setting.

“A New Loyalty Base” by Stephen Inniss makes a great observation that back in the 1E (and even 2E) days, Charisma was often disregarded in favor of “informal estimates,” ignoring reaction rolls altogether as they may “interfere with the dramatic structure of an adventure.” For example, if a reaction roll has the fearsome guardian of a dungeon’s treasure reacting to the PCs with friendliness, suddenly they are not so fearsome. As such, a high Charisma score was often seen as a waste (unless you happened to want to play a paladin or druid).

In the process of explaining how confusing the process of reaction rolls and morale checks can be—the relevant tables and rules are spread out over different page and in different books, and rolling high is good in some instances but bad in others—Inniss manages to provide revised and consolidated rules that uses a unified d20 approach (14 years before 3E would do that for the entire game).

Of course, this is followed up by two pages of tables and modifiers steeped in AD&D race-based assumptions, so not quite that forward looking.

Personally, I think a simple reaction/morale system is a good thing for when an NPC’s attitude is unclear. But otherwise, a seasoned DM should be able to determine it based on what they know about the creature/NPC in question, the specific context for the encounter, and its particular motivations.

“The Six Main Skills” by Jefferson P. Swycaffer is not about what we call “skills” in the current game, but about the six ability scores. Rereading it now, it is not only boring but I find discussing D&D’s stats in real world terms to be a waste of time. You just have to accept that D&D is a game with abstracted ways of measuring what are ultimately complex categories of human (and demi-human) ability. My reaction to this article is compounded by Kim Mohan’s follow-up article, “Room for Improvement,” which examines the issue of increasing ability scores. I think a general move away from training as a required part of D&D character advancement and simulationism as a goal, along with the eventual adoption of built-in ability score increases makes this article feel even more outdated than most.

Rather than a dedicated “Role-Playing Reviews” section, there are two game reviews that get their own articles. Ken Rolston’s review “Pendragon: Arthur Would Approve” is glowing. He writes “the best designed, most attractive, and most effective traditional role-playing game I have ever seen.” The other review—by Eric W. Pass—“Harn was Just the Start” reviews Columbia Games’ supplements for the Harn setting rather positively.

There are two books of note (for me personally, at least) covered in this issue’s “The Role of Books.” The Misenchanted Sword by Lawrence Watt-Evans is a book that I looked for in bookstores for several years based on this review. I would eventually find it and read it repeatedly (I wish I still had it) but even before then I incorporated elements from it gleaned from the review into my D&D campaigns. Watt-Evans’s Esthar books (of which, this is one installment), for all their weaknesses (and there is an undercurrent of Piers Anthony style sex creepiness in them), were a huge influence on my games, and I included a version of the titular magic sword in one campaign and elements of “A Single Spell” influenced the basic conceit of my “Out of the Frying Pan” campaign. What I like most about the Esthar books are their shared world’s D&D-like existence of multiple competing modes of magic and how each book stands on its own with only the occasional easter egg cameo for those who have read other books in the series to enjoy.

There are two books of note (for me personally, at least) covered in this issue’s “The Role of Books.” The Misenchanted Sword by Lawrence Watt-Evans is a book that I looked for in bookstores for several years based on this review. I would eventually find it and read it repeatedly (I wish I still had it) but even before then I incorporated elements from it gleaned from the review into my D&D campaigns. Watt-Evans’s Esthar books (of which, this is one installment), for all their weaknesses (and there is an undercurrent of Piers Anthony style sex creepiness in them), were a huge influence on my games, and I included a version of the titular magic sword in one campaign and elements of “A Single Spell” influenced the basic conceit of my “Out of the Frying Pan” campaign. What I like most about the Esthar books are their shared world’s D&D-like existence of multiple competing modes of magic and how each book stands on its own with only the occasional easter egg cameo for those who have read other books in the series to enjoy.

The other book of note reviewed in this issue is Saga of the Old City, a fantasy novel by Gary Gygax set in Greyhawk. The reviewer praises the boss’s book, the one criticism being that its attempt to combine “the personal chronicles of Gord of Greyhawk” with the “almost scholarly treatise on [Greyhawk]” does not always work since they require “incompatible prose styles.”

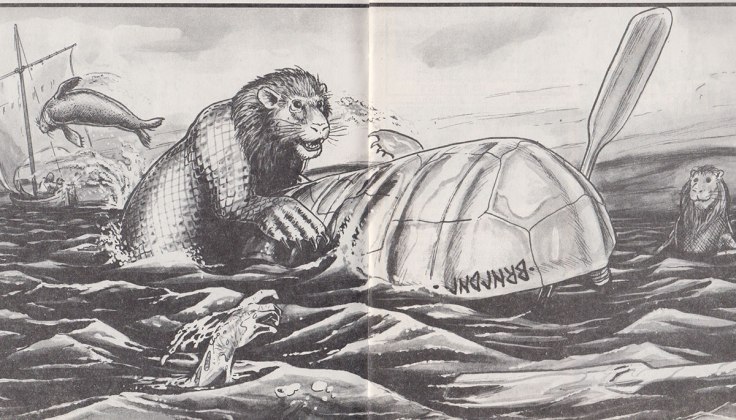

“The Ecology of the Sea Lion” brings our Greenwood Count to fourteen.

When I think about D&D Sea Lions I think about how in 3E they tried to rename “Sea Lions” as “Sea Cats,” the presumable reason being that “Sea Lions” are a real-world animal and there could be confusion. As far as I’m concerned, however, the real absurdity is that the people of our world saw what were obviously a kind of barking sea dog and called them “lions.” To put it another way that might be clearer, it makes more sense to me for D&D sea lions to be actual lions that live in the sea than to call them “sea cats” so that actual sea lions can also exist, when “seal” is right there to do all the necessary work to describe the real-world animal in the fantastical one. Elminster makes the same basic argument in “The Ecology of the Sea Lion,” except the part about 3E, because not even the wizard of the Realms could have foreseen that iteration in 1986!

Sticking with the nautical theme, “For Sail: One New NPC” by Scott Bennie introduces the Mariner, an NPC class of almost superheroic sailing ability. I used this class quite a bit in my games as NPC and as PCs in troupe play (each player having four or five PCs at a time). Like most non-fighter classes of the time, the article bends over backwards to explain the class’s weapons limitations: because ship-to-ship fighting is in close-quarters, mariners can only ever learn from a certain list of weapons and no others. In terms of abilities, the mariner gains parrying and disarming maneuvers and is really good at swimming and holding their breath. They also get rules for their expertise at piloting ships, climbing rigging, knowledge of sea lore and languages, and eventually undersea combat and the command of crews. Thematically speaking, I still kind of love it and wonder if there is a good fighter or rogue subclass that would fill this niche in a book I am unfamiliar with (I don’t buy much 5E optional material).

There is not one piece of accompanying art with the Mariner article, which in my estimation says a lot about Dragon Magazine budgets and priorities.

“Economics Made Easy” could perhaps be one of the most influential articles on my style of DMing and worldbuilding. Re-reading it now, I was taken aback by how much of it still guides my general feel for what a D&D world should be like in terms of determining prices and scarcity and the effect the lavish spending of successful adventurers can have on a local economy. In the article, Ralph Marshall argues for and describes what he calls “economic illusionism.” In other words, it would probably be impossible to construct an actual living economy for a D&D world and the work that would require if you could would reap little benefit. However, by keeping in mind the economic consequences and possibilities of money and treasure in the campaign, the DM can extrapolate in order to create opportunities for both verisimilitude and dramatic play. That’s what I got out of it anyway. This is why in my current Revenants of Saltmarsh games the characters have found weapons in the market rarer and more expensive. The town’s preparations for a sahuagin invasion means most available weapons have already been bought up. Marshall may suggest keeping track of some simulated interest rate, but I never needed to actually do that to introduce fluctuations in the price of gear in the Player’s Handbook. As far as I’m concerned, the gear prices in the PHB are starting prices for the sake of character creation. Once the game begins they are at least suggestions and at most a base price to work from.

Anyway, Ralph Marshall, wherever you are, thanks for helping to guide a 15-year old D&D freak’s games for the next 37 years and beyond.

Anyway, Ralph Marshall, wherever you are, thanks for helping to guide a 15-year old D&D freak’s games for the next 37 years and beyond.

There is an ad for Car Wars on the second page of that two-page article. I played a lot of Car Wars starting around 1986 and would for the next few years. God, I miss that game and wish I could find people to play it with me.

The center of Dragon #107 is given to “More Dragons of Glory,” which provides advanced rules and more options for running the 1980s equivalent of the Dragonlance: Warriors of Krynn game, DL11 – Dragons of Glory. The module contains “a complete and self-contained simulation game” but based on how it was packaged does not have the same production quality as the contemporary version. I have never run Dragonlance stuff and never owned this module, so I am not in a position to rate what it offers.

“When the Rations Run Out” suggests another complex subsystem for AD&D—going without food or drink.

“Doomsgame” is a piece of short fiction in which RPG characters discover they are part of a game.

The ARĒS section of Dragon #107 includes “Mutant Fever,” which provides a system for health and disease for Gamma World, “One in a Million” (by future Dungeon and Dragon mag editor-in-chief, Roger Moore), about constructing a supers campaign with advice not tied to any particular RPG system, and “Tote that Barge,” the sci-fi equivalent of “Economics Made Easy.” As for that last one, the only sci-fi game I’d run at the time was Star Frontiers, and I ran it as a space adventure game. As such, I didn’t find the article as useful. I guess I found space economics harder to fake than the pseudo-medieval kind. The Marvel-Phile presents stats for Omega Flight, and “The Crusading Life” provides suggestions for what life is like for superheroes between their adventures. It is what I call the “Spider-Man Effect,” when the hero’s life and the personal stakes of heroing is at least as interesting as when the character is taken to a global or cosmic level. Heck, give me a story about a hero struggling to pay his rent while the Rhino is on a bank-robbing spree and his girlfriend is working as a teller over a story about the Infinity Gauntlet any day of the week.

There was more supers content in this issue than I remember, but that is probably a result of time and not really running any supers games until a few years after this issue came out and not with any consistency until the 90s and 00s.

In Dave Trampier’s Wormy, the game-playing little tree trolls end up hunted by diabolic-looking ogres and in Larry Elmore’s Snarfquest, Snarf and friends are separated while fleeing a ghost.

And there you have it, an issue of Dragon that at first glance did not seem particularly memorable but that in paging through it, ended up with a lot more going on. Furthermore, there was a six-month gap between when I initially re-read this issue, taking notes for this post and when I sat down to actually write it but those notes were so good that writing this was not only not as onerous as I feared this project might have become for me, but the process re-inspired my drive to continue to dig into my collection of Dragon Magazine. So, I will see you in a few weeks with a look at Dragon #109 (May 1986).